Turkish writer and analyst

(whose Substack you must follow) recently penned a great post on "The Legacy of the Muslim Boomers." The piece responded to articles by yours truly and , namely my last post on how 10/7 radically changed my geopolitics and Shadi's WaPo column on liberalism, faith, happiness, and choice.Now I will say off the bat that I found Selim and Shadi's contributions frustrating to read. But that's precisely why they're also both so worth your time. Good writing stirs strong emotion.

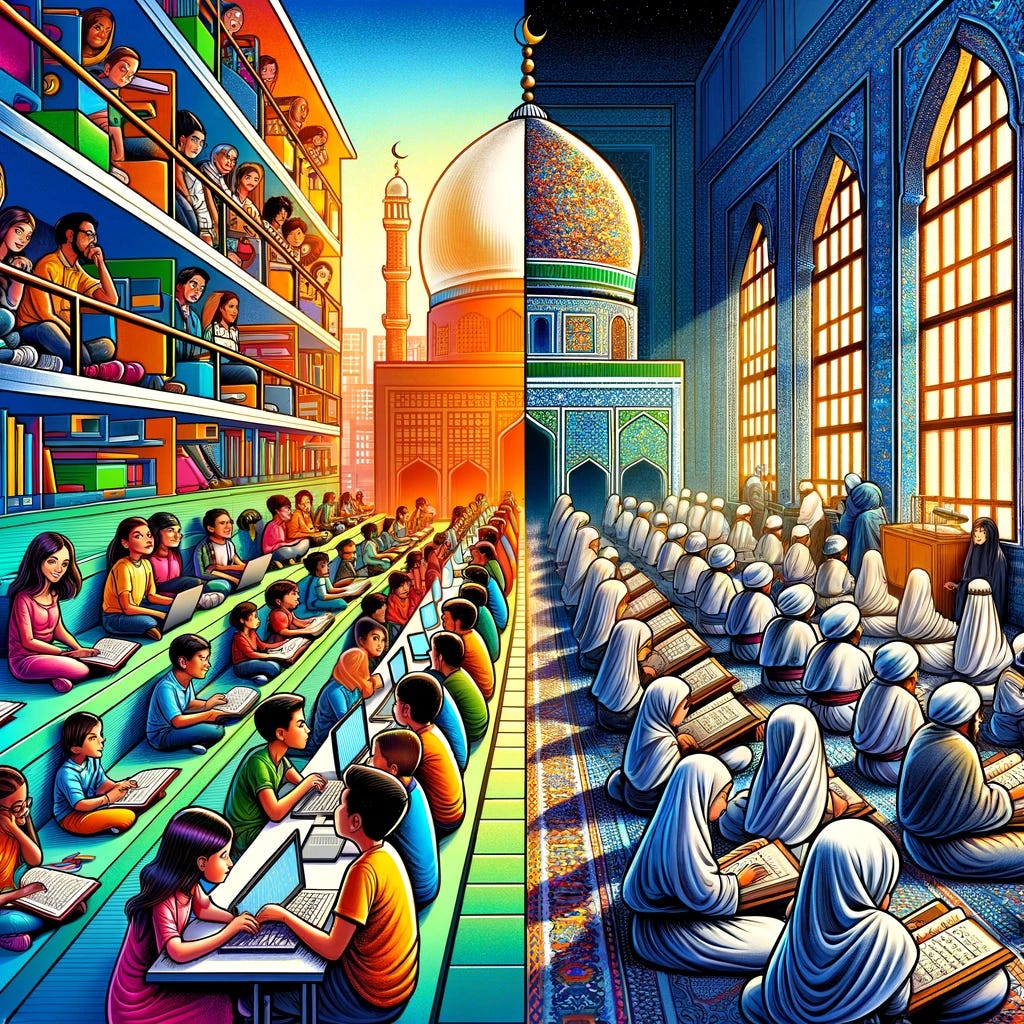

Before getting into it, it's worth stepping back. We're three Muslim guys working through this post-10/7 moment in similar, yet different ways. We're looking at current affairs through our analyst eyes, sure. But we're also not limiting ourselves to that—we clearly see the great value that lies within the anecdotal, and we're not afraid to extrapolate from there and gesture at what we feel may be broader trends. That’s refreshing. We're speaking about our own childhood experiences, our parents, our religious and secular upbringings, and we're doing so honestly. So much more of this is needed, as most of the writing on the "Muslim street" in policy spaces are written by people who have zero organic presence in the community. And though I gather we come from very different backgrounds (Egypt, Turkey, Pakistan), at least we're speaking from lived experience, and not just theory.

After reading the above pieces, I needed several days of brooding to work through my feelings. But after having given it a think, I regret to inform Shadi and Selim that they both stand accused of the high crime of being boring. Boring to the point where—and I mean this from a place of heartfelt concern as a brother in faith—that I genuinely pity their approaches, one which leaves them either existentially confused or cynically donning faith "like a suit of armor" for its worldly utility. If this is the inheritance of our Muslim boomer parents, I feel even more validated in kicking it to the curb.

This will of course require further elaboration.

Let's start off by looking at how they engage the question of what a liberal education does. Shadi, to his credit, is examining how his life choices shaped his subjectivity, his very spirit. He's come up in liberal institutions and has a successful career (say mashallah), and he attributes at least a part of that success to those liberal sensitivities which now make up a significant part of who he is. But those very sensitivities have a dark underbelly: existential dread. Could he have walked a different path? This is the key passage, with key words highlighted.

I can imagine being both more religious and religiously conservative, but I suspect it would have required an upbringing that was less encouraging of education, ambition and intellectual curiosity. It doesn’t work this way for everyone, but I have often felt a certain tension between the comfort of religious rules and ritual and the excitement and wide-openness that come with the removal of constraint. I got older. The more I learned, the more I knew. And the more I knew, the more I had doubts about what I had known before.

This trade-off might have been worth it, but it was a trade-off nonetheless. Once you are exposed to the secular world — a world where personal autonomy and experience eclipse tradition — it becomes harder to return, even if you wish to.

...

As the hold of religion weakens, it becomes harder to understand whether our choices have been the “right” ones. Our standards and judgments no longer refer to traditions; they become self-referential. This sense of endless choice injects into our lives an undercurrent of nearly perpetual panic, of never knowing whether we’re living as we should. Yet we become so used to our freedom to choose that we insist on retaining it regardless of the consequences.

Selim also focused on this passage, asserting that a "liberal education unlike a technical education mostly ruins one’s chances of being deeply pious. There are exceptions, but not many of them." I will take this assertion at face value (although this has not been my experience, and I wager there are more than just a few exceptions).

What both Selim and Shadi are saying is that there's a dichotomy at play. Choose liberalism and receive better "education", more "ambition", "open-mindedness", and "curiosity", but lose "piety", the "comfort of religious rules", and certainty in Truth ("more doubts", as Shadi puts it).

Or, you could choose tradition and religion. Then you get to keep God as your teddy bear.

Snooze. Is the discourse really still stuck here? Though Selim thankfully distances himself from "new atheist disdain" of religion, he and Shadi both seem to trade it in for something not that much different: a kind of "liberal smugness." What do I mean by that? It's not that I think either of these guys actively dislike Islam or conservative Muslims, I'm not saying that at all. But I am calling it arrogant and a bit of a cope to essentially blame liberal enculturation (in Shadi's case) or the excesses of "reactionary [Turkish] nationalism" (as Selim mentions) for why one can't maintain "conservative" piety.

I also have to comment on the predictable aversion for "rules and ritual" exhibited by both these authors. It never ceases to amaze me just how successfully Western liberalism has mainstreamed the Christian idea of breaking free from the yoke of the law (what later Western orientalists would pejoratively term “Semitic legalism”). But now, in our secularized world, we drop the Law not to buy us salvation, but personal autonomy and freedom. In this way, personal freedom becomes the closest thing to salvation for a debased people who believe not in an afterlife.

Though Shadi and Selim grew up on opposite ends of the world, these deeply-embedded liberal assumptions ensured they would both reach the same conclusion: law restricts muh freedom, and this is bad because freedom is an unmitigated good. Nevermind the countless examples of brilliance and creativity by people who strictly adhered to the law—their selfhood was restricted in a fundamental way. They just didn't know what we free people know today.

Sigh. This is just such a trite take. That earns you both ten uncle points. (Sorry, I don't make the rules).

But in defense of the Muslim boomers and their dutiful children, not all of them embraced this (false) dichotomy. Most uncles and aunties I know (especially those who were spared all these fantastic benefits of a liberal education) do not adopt neither a smug, liberal style nor an aversion to ritual. When they do fall short—as we all do—they bravely sit with that. They eventually own up to it. They feel remorse (nadamah), they ask Allah for tawfiq to do better, they make tawba. That is a sign of gnosis (ma'rifat Allah), of knowing who Allah is. They're people who came from societies that teach you to focus not on your youness but entirely on His Hisness. To sit face to face with Allah at all times, even when you're not at your best. That is true courage.

Liberals, by contrast, find it very difficult to process guilt, to process sin. They would sooner adopt all types of laughable reformist contortions (or, as Selim admits to his piece, turn to agnosticism and adopt faith as a suit of armor when convenient) rather than just take the L with grace and vow to do better next time. To paraphrase a hadith, a people who feel no shame are sociopaths, they should just go ahead and do whatever they wish.

I went to a big party school a few hours away from home. I could have done whatever I wanted and swept it under the rug. But, like Selim wrote about in his piece, college was when I too had to decide for myself if I was going to do this Islam thing f'realz or if I'd just become a floozy. I made my choice, and through Allah's great bounty, I've never wavered since.

It's been my experience that the liberalized mind—drunk off endless choice—stumbles into an extreme level of interiority. Anthropocentric "self-discovery" gets taken to such a point in Western societies today that it's now resulting in widespread neuroticism and mental illness—liberalism as pathology. That is the abyss, as far as I'm concerned. A healthy religious society, by contrast, is so thoroughly theocentric that it keeps the abyss at bay.

Which brings me to why I find Shadi and Selim's insistence on fence-sitting in this way hard to comprehend. I hope I'm not constructing a strawman here, but what utility is there in all this navel gazing? What are you after? Getting to sleep in instead of waking up for Fajr? Juicy Big Macs? Poontang? Your lib friends won't think you're cool anymore? It's got to be more than that, surely. These are both genuinely smart guys. I will be generous and presume that my dear interlocutors have better reasons for reluctantly maintaining liberalism.

Perhaps they feel deep down that if people weren't brought up to be good autonomous liberal agents, that progress might stop, that we might not be as innovative or creative or risk-taking. Maybe illiberal societies would be "bad" for individuals, given that they believe in silly things like shame and honor, praying 5x a day, being loyal to your parents, and other autonomy-limiters. Or, perhaps, remixing Churchill, they feel that "liberalism is the worst form of self-direction, except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time." For the life of me, I cannot figure out what’s appealing here.

At this point, it is all just so tiring. I predict that as Western societies continue to decline, the reluctant liberal will seem just as out-of-touch as boomers seem today. To be a half-ass liberal will come to be seen as a decadent luxury of that brief unipolar moment America enjoyed following the Cold War (as Selim notes, it is this very period in which the boomers raised us!). But as actors of all types scramble to make the coming new world (and it is coming), those with blithely-held ideological commitments will be booed off the field. Be a full-octane liberal like B. Henri Levy (puke), a fully-committed person of faith, an anarchist, something. But join a team. Don’t be a navel gazer. "Shit or get off the pot!" as my football coach used to say. I think

, Shadi's co-host at , would agree with me here.Remember: believing in something with your whole chest doesn't mean you will have a perfect implementation of those beliefs. I certainly am not a saint. I have good days and I have very bad days. But ever since Islam "clicked" for me, I see the world as animated, alive, and aware.

This is not just a belief of mine, it is an experienced reality. I see my very thoughts and inspirations and feelings as emanating not simply from my own tiny and insignificant reservoir. Some of my thoughts are angelic inspirations, from the Highest Assembly (al-mala' al-a'la). Some of my thoughts are whisperings of the Devil, and I can recognize that. Some are from my own ego, and I intuit that as well. Some of you may find it crazy, but I even get my dreams interpreted―they are incursions into our reality from the Imaginal Realm, the ‘alam al-mithal. And when engaging in seemingly-mundane activities, like drinking a cup of coffee, I feel Allah ﷻ instantiating all that complex flavor and smell within my body. And so on and so forth.

I have found life so much more pleasurable this way, to the point of intoxication. There have been times when I have been so immersed in this remembrance and recognition of Allah ﷻ that, for brief moments, the fog of my own selfhood lifts entirely, and there is no longer an "I" who could forget Him. There is only Him. It is in these moments of mi'raj where one ascends away from the self towards Him.

This has gone on for far too long. I had wanted to touch on several other things, such as how my generation has been robbed of any serious exposure to real tasawwuf and suhba, the impoverished state of Muslim educational institutions, and more. But that will have to wait until another time.

I will leave you instead with that famous quote of Teddy Roosevelt on the virtue of being the "man in the arena." That is all I have ever wanted to be.

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

Islam does not need the Cancer of 'Liberalism,' which has shown itself post-October 7 to be a Bloodthirsty, Nutcase, Antihuman, pro-Djinn ideology. What Islam needs is an Ascension & revival:

& such a thing will not happen until Steps are taken to Restore the Khilafa with Al-Quds as its Capital.

I feel like there was a point in all of our lives where we wanted to pretend to be on their side and enjoy the lifestyle that came with it. Our parents brought this strange combination of culture and religion that seemed so easy to shun as something from back home. We knew we’d never really fit in with the other kids but it was worth a try. Then eventually you realize it was all a scam. So many of these American liberals are depressed and on anxiety medications, their marriages are crumbling and they are lost in this strange world of work and leisure being the only things they have. Living for the weekend and trying to climb the corporate ladder. That’s it? Once I started reading about Islam and seriously practicing the deen I no longer felt the inferiority I did before. I felt peace.