Towards a Muslim sartorial agenda—an opening salvo in four scenes

We have forgotten what it means to dress. As the deepest living repository of traditional clothing, Muslims have a responsibility to re-dignify the human. Enter the Muslim Sartorial Agenda.

"Turbans are the crowns of the Arabs."

Hadith attributed to the Messenger of Allah ﷺ

Scene 1:

We get up from our meal, my cousin leading the way. I was six years old, visiting Pakistan. "Let's have you meet our local molvi," he said to me in Punjabi. I waddled over in my jeans and t-shirt, a total American kid. We entered the local masjid, and we chitchatted with the kind molvi sahib. I don't remember anything from our conversation, except for the advice he very seriously imparted to me at the end. "You are going to grow up in America. Don't forget who you really are. When you're in the comfort of your own home, wear shalwar kameez." I left feeling confused. What the hell did shalwar kameez have to do with Islam and being Muslim? Perhaps because of how weird it came off, the entire scene remained seared in my mind forever.

I can't explain why, but shortly thereafter I began to follow his advice, eschewing pajamas whenever for SK. Over time, this funny habit bubbled up into a deep and abiding love for traditional Muslim clothes. Whenever I travel now, I collect various hats, cloaks, turbans, jubbas, whatever I can get my hands on. As I grew older, I began to think more deeply as to what makes for truly "Muslim" clothing. What principles and goals motivate their design? I couldn't put my finger on it, but there was something unifying behind them.

Scene 2:

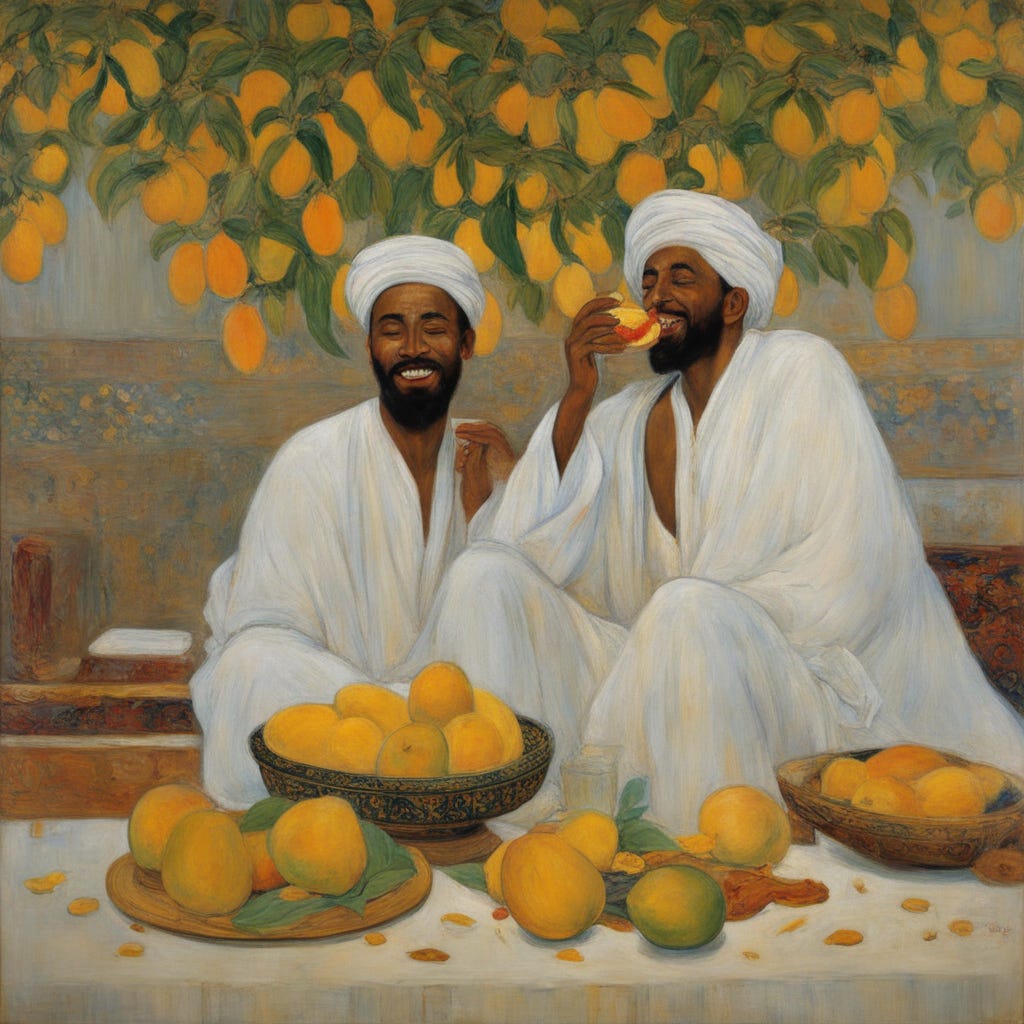

I'm in a Zoom class with a shaykh. We've been reading a text together in a small group. We pause at a passage that particularly delighted him. He looked up at us. "Have you ever seen an Englishman eat a mango?" said the shaykh. "He sits down at a nice table, he inspects the mango. He takes out his knife and fork, and he slowly and carefully begins peeling. He dices the mango into bite-sized pieces, throws away the peel, sits back down again, and only then starts eating."

I wasn't sure where this was going.

"But how do Muslims eat mangoes? We ravish the mango. We give it a rough chop, and we slide the innards right off the peel with our teeth. We get messy, we let the juices roll down our chin. It's a whole thing."

"Now, technically, both people ate a mango. But who really experienced it? Who really knows its reality? Who is truly alive? Obviously, the Muslim is. This is the nature of the difference between the orientalists and the true inheritors of prophecy. It is precisely why the former will never truly penetrate to Islam's reality."

Now I understood.

Scene 3:

I'm working in a very standard fare office environment in a major American city. It was one of those where you came in every day with slacks, dress shoes, button shirt. Ties and a blazer on special days, like when we had a guest speaker, holiday party, that sort of thing. On one particular Friday, however, I decided to wear a long tunic from South Asia called a kurta, basically the top part of a shalwar kameez.

I didn't think much of it; I wore it not to express muh diversity so much as I wore it because I was lazy and all my shirts were dirty. The words of the molvi from 2 decades ago did not factor in this time. Plus, it was Friday, and I had to head to jumu'ah prayers around lunchtime anyway, after which I would go home ("Summer Hours").

A few weeks later, however, my boss pulled me into his office for a chat. "We need to talk about how you're dressing around here," he said. "You can't deviate from the standard look. When you dress...differently...management may get the impression that our department doesn't run a tight ship. And that can affect our budget." I was kind of taken aback, but did not protest. I always made sure my dress shirts were ready to go after that.

Scene 4:

I come home from a long day at work. It's been a sweltering day, and I can't wait to rip off my pants and dress shirt and exchange them for something more flowy, airy, less rigid. It's time to for prayer soon, however, and I can't help but sigh to myself. I don't particularly want to pray or even think about anything having to do with Islam just this now.

My jobs have always been me analyzing Islam, current affairs in the Muslim world, writing about Islam and/or Muslims, etc—all for non-Muslim employers. Kind ones, no doubt, but non-Muslims nonetheless. I've been in this funny position for years where I have to speak about my own faith in a detached, academic fashion. It's hard to describe, but it's exhausting. It's exhausting because you are always suppressing inside what you truly believe. You do that enough times and it begins to change you, you start to view your own faith like an orientalist might, with a kind of voyeuristic curiosity from a distance.

I let the sigh out fully, only to see the penetrating face of the molvi flash through my mind. His strange advice to me years and years ago clicks right in that moment. I finish changing into my SK. I then walk over to the bathroom and make wudu. I take out a turban from out the closet and slowly begin wrapping it around my hat in front of the mirror. For some reason, this feels right. I apply some scent to my clothing. I face the qibla, raise my hands, and begin to pray.

I am eating a mango with my hands.

I shared the above scenes to begin a series of posts unpacking my thoughts on what I am calling the MSA—the Muslim Sartorial Agenda. This topic is too-often seen as cosmetic (literally), when in actuality it is of extreme importance, both exoterically and esoterically. This is even more so in our time, when Western trousers and dress shirts and uncovered heads have become a global norm.

Muslim societies, however, may be the one human grouping left with a sizable population of men and women who have retained traditional clothing at a societal level. Only we can set things right. Everyone else is far too gone.

I want to open up a more serious conversation about what clothing represents for humanity today. I want to speak about the dignity conferred by clothing, the responsibility Muslims have towards humanity at large to exemplify civilization and piety through noble garments which reflect noble character. I want to move the conversation beyond just women and hijab, which is just the starting point. And though I want to speak to both genders, I have a particular interest in having a conversation with Muslim men as to our sartorial responsibilities. We have all seen that Muslim guy in London or NYC with shorts (often above the knee...) and a polo and a receding hairline...holding hands with his niqabi wife. That's the state most of us are in, one of total deracination and a complete lack of awareness of The Way.

This is enough of an introductory post. In the comments or in an email, please do send me sub-topics you'd like to see addressed in future entries for this series on the Muslim Sartorial Agenda. I have my own interests, obviously, but I want to speak to your concerns as well, to the extent that I am able.

If this is a topic that really interests you (and you can write well), consider pitching a guest post via email.

In Faith,

Drago

This is actually an important point. How we dress is about aesthetics, sure, but also about climate, culture, and values. Islamic clothing that is loose and flowy but also dignified, is about being comfortable in a hot climate, but also experiencing the world in a direct way. The Westerner who eats a mango with a knife and fork also wears buttoned up clothes, which work for a cold climate, but also reflect a buttoned up way of experiencing the world.

At the same time, our clothes reflect our values. We wear long flowy clothes but we don't show skin.

This also explains why I'm mildly irritated by the Senate changing its dress code to let John Fetterman wear sweatshirts and basketball shorts on the Senate floor. In his culture, a suit signals respect and decorum.

I think the global urbanization is typically creating a monoculture including a shorts/t-shirt uniformity that carries a certain attitude and approach to life